For almost all of my work on retirement withdrawal rates, I’ve assumed a constant inflation-adjusted withdrawal rate strategy. That is, the withdrawal rate is defined as an amount of income withdrawn in the first year of retirement as a percentage of retirement date assets. This income amount then adjusts for inflation in subsequent years. Since writing an

article on GLWBs for

Advisor Perspectives last year, I’ve had the capabilities to consider other variable/dynamic/flexible withdrawal rate strategies, but I just never got around to doing it. But finally I’ve decided its time to start having a look, especially in light of the comments at my last

blog entry.

This is still quite preliminary, but let’s have a brief look at another popular withdrawal rate strategy, which is to withdraw a constant percentage of remaining assets. Then, a 4% rule means you withdraw 4% of whatever remains each year. This is not the classically defined 4% rule, keep in mind. Your withdrawal amount increases (even in real terms) above the initial amount when the portfolio grows (in real terms) from its retirement date value. Your withdrawal amounts decrease when the portfolio loses value.

With this approach, you cannot define failure in the classical way of running out of wealth, because you never actually run out of wealth. It is just that your withdrawal amounts get smaller and smaller as the portfolio value gets smaller and smaller.

So to think about failure with this sort of rule, you must decide on an acceptable threshold for how far you are willing to let your retirement spending power drop over time.

Let’s have a brief look at a couple of figures. I’m using 10,000 Monte Carlo simulations calibrated to the historical data (large-cap stocks and intermediate-term government bonds). See my

last blog entry for some important caveats about this. Retirement date wealth is 100, and I will look at spending streams over time for different withdrawal rates defined as a percentage of remaining assets withdrawn each year.

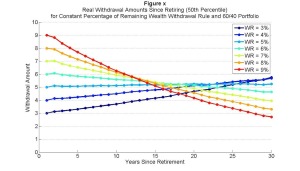

This first figure looks at the median spending amount in each year (in inflation-adjusted terms) for different withdrawal rates for a 60/40 asset allocation. You have a 50% chance to spend more than this, and a 50% chance to spend less. With retirement date wealth of 100, a 9% withdrawal rate lets you spend 9 in the first year. But this high spending rate tends to eat into your capital, and continuing to spend 9% of your assets leads to lower and lower withdrawal amounts in subsequent years. On the other hand, a 3% withdrawal rate is sufficiently low that you can expect, on average, to enjoy increased spending over time. A 5% withdrawal rate is about the rate that will keep spending amounts constant over time.

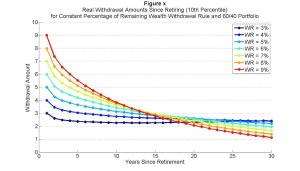

But that is the median case. Risk averse retirees will be worried about what will happen in worse scenarios. Now let’s look at the 10th percentile. You have a 90% chance of doing better than this, but a 10% chance of doing worse:

Surprisingly, none of these withdrawal rates maintains the real purchasing power over time. I’m guessing this may be because since you are always withdrawing the same percentage, you are always somewhat vulnerable to negative returns. It probably makes sense to follow some sort of ceiling on how high you let spending go when market returns are high as William Bengen and Jonathan Guyton have considered in the past and I will consider later on as well.

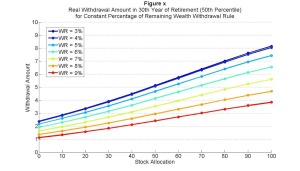

Next, let’s check the spending amount in year 30 for different asset allocations. Here is the median case:

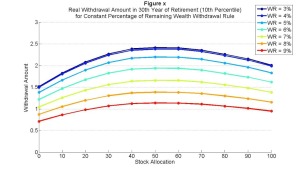

Stocks have higher expected returns and more volality, so on average in the median they can support the higher spending streams for any particular withdrawal rate. But again, a risk averse retiree won’t focus on that. Here is the 10th percentile:

Something which has kept showing up is that there isn’t much difference between 3% and 4% withdrawals. For all of these withdrawal rates, a balanced portfolio tends to support the highest spending in year 30 in this 10th percentile outcome.

So, this is just the very beginning of a new avenue of income strategies for me to consider. I will be writing more about this again in the future.